By France specialist Jesse

Normandy has long stood as a pivot point of history. Endless waves of armies and invaders — from the Vikings to the Allies — have left an indelible mark on the region. This turbulent past, combined with its geography, give Normandy a culture that is distinct from the rest of France.

Here, you’ll find wine overshadowed by cider, Celtic-influenced half-timbered houses, and churches built with Viking techniques, as well as the cloud-dappled skies and pastel-hued landscapes that helped inspire Impressionism. It’s also a place of pilgrimage, where people come to pay their respects to the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who died in the vital but harrowing D-Day invasion.

Things to see and do in Normandy

Honfleur

Perched at the mouth of the Seine, this port town was once a commercial hub that made its money from tariffs and the salt trade. Today, it attracts both weekenders from Paris and artists drawn by the natural clarity of the light reflecting off the sea.

Vieux Bassin (Old Port) is still the heart of the city, filled with bright sailboats and lined with cafés that spill out onto the quays. An irregular row of tall, narrow buildings faces the port, many faced or roofed with slate to protect them from the elements. You’ll also find the Lieutenance, the 18th-century residence of the governor and the last surviving remnant of the town’s medieval fortifications.

East of the port, the Enclos’ is the part of town that used to lie within the medieval walls. I enjoy ambling through its cobblestone streets and crooked lanes, admiring the hodgepodge of fisherman’s cottages, venerable stone mansions and maisons à colombage (half-timbered houses) that cant at unlikely angles.

Within the maze of narrow streets, you’ll find Saint-Catherine’s Church. During the rebuilding that followed the Hundred Years’ War, stone was at such a premium that the residents built a wooden church using the techniques bequeathed them by Viking shipwrights. The result resembles the hull of an overturned ship, curved ribs joining overhead to form a high arched ceiling.

Built away from the main building, the church’s bell tower seems like a weirdly spiky afterthought supported by inelegant wooden buttresses. Historians speculate that the distance was to protect the town and church in case a lightning strike started a fire.

Honfleur is also the birthplace of Eugène Boudin, one of the first French landscape painters en plein air (outdoors). Called the ‘king of the skies’, he was entranced by the play of light off the river and ocean and the way scudding clouds cast moving shadows on the water. He imparted his love of movement to his friend, Claude Monet, who often came to the town to paint. In fact, it could be said that Impressionism was born in Honfleur.

Bayeux

An hour’s drive west of Honfleur, Bayeux is a pretty town that managed to avoid bombing in World War II. The mishmash of gray-stone buildings date back centuries and little stone footbridges span the river that winds through town. However, most people visit to see the best-known piece of embroidery in the world: the Bayeux Tapestry.

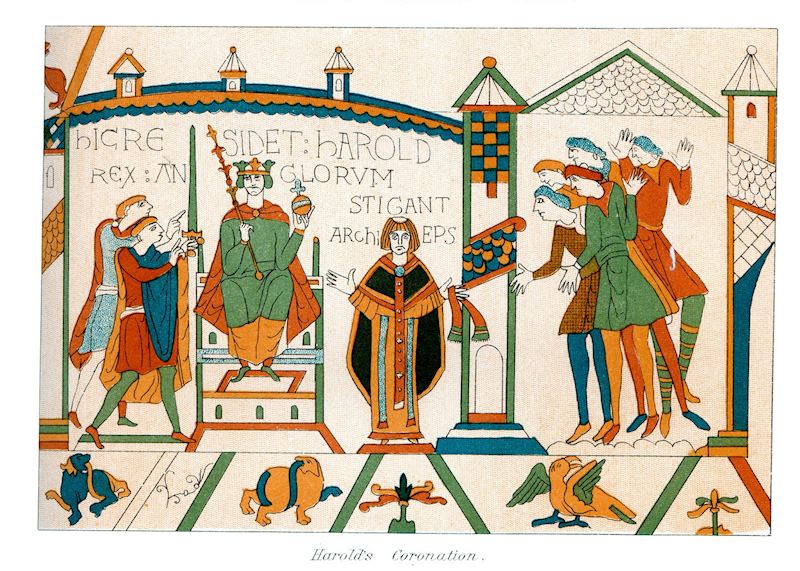

The tapestry is both vast — 70 m (230 ft) long — and venerable: it was created just a few years after the Battle of Hastings to commemorate King William’s conquest of England. Technically, it’s not a tapestry — the exquisitely detailed scenes are not woven into the fabric but instead embroidered in with vegetable-dyed yarn in tiny, precise stitches.

It’s displayed in a horseshoe-shaped case at the Musée de la Tapisserie de Bayeux, which offers a clever audio guide that brings to life the tapestry’s history, artistry and wit. I laughed out loud when the narrator paused to point out that one of the figures isn’t wearing any shoes.

Intended for an illiterate audience, the tapestry depicts the events of the conquest from the Norman point of view, enlivened with gory violence and ribald moments. There has been almost 1,000 years of (prurient) speculation about the reason behind a leering naked man in the border near the unexplained inscription that translates to ‘Look here! It’s a clerk and Ælfgyva’.

Mont Saint-Michel

Roughly a 90-minute drive from Bayeux, Mont Saint-Michel rises from west Normandy’s tidal marshes like a fantastical city better suited to a Hollywood blockbuster than the sleepy French coast. Its towering spires and sturdy ramparts occupy a small island in a bay with enormous tidal variations — as much as 14 m (46 feet).

The granite outcrop is occupied by an abbey at the very top and fortifications near the waterline, with narrow stone-paved streets and medieval buildings on the rocky slopes between. Walkways and stairs curve up the island in a large spiral — I suggest wearing sturdy shoes to navigate the steep and sometimes slippery paths.

In the silty marshlands that surround Mont Saint-Michel, sheep forage on the succulents known as samphire, which grow in the tidal flats. These sheep are prized for their tender, savory meat, a result of the high levels of salinity and iodine in their fodder. The name, agneau de pré-salé, literally means ‘pre-salted lamb’.

Normandy’s D-Day Beaches

Standing on Normandy’s long golden sands, it can be hard to believe that these serene stretches were the setting of one of the biggest battles in World War II. Vast and complex, the Allied invasion of Normandy moved huge amounts of both men and material from three nations to five different sites strung out along the Norman coast.

Visiting the beaches can be complicated, logistically speaking. Normandy is dense with sites relating to both D-Day and World War II in general, so I’ve just highlighted some of the most compelling sites. They include the five main D-Day beaches as well as cemeteries, former Nazi fortifications and historic Norman chateaux swept up in wartime activities. The best way of exploring it all is with a private driver-guide, who can navigate the region’s roads and help provide context for each site.

This section of a Normandy trip can also — unsurprisingly — be overwhelming emotionally. My guide, Sarah, had a knack for understanding when to explain the history behind what I was seeing and when to offer me some space to deal with the waves of emotion that crashed over me.

Omaha and Utah

I saw Omaha Beach a thousand times before I saw it for the first time. Because it’s been endlessly captured in newsreels, photos and movies, I felt the shock of recognition everywhere I turned. The beach itself is long and deep, and very little of its battle scars are visible. However, Sarah explained to me that the sand under my feet was, in fact, about 4% shrapnel and debris from the invasion.

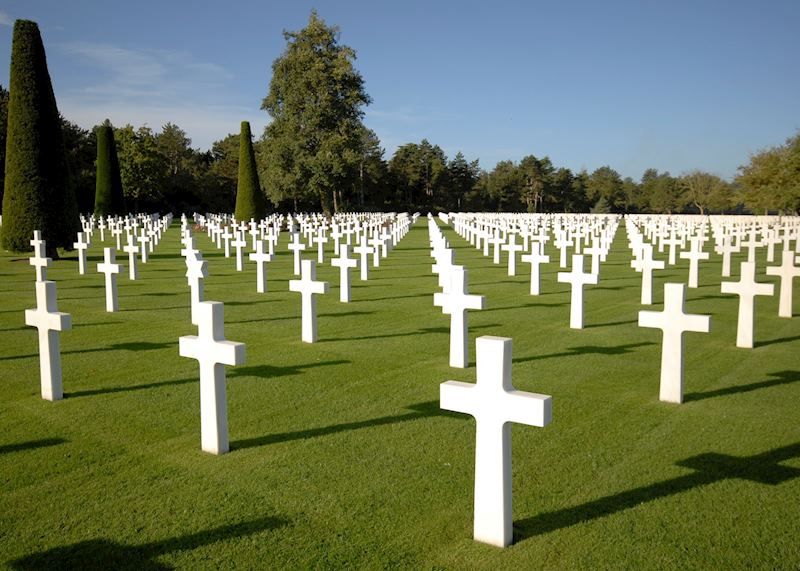

Situated on a bluff overlooking the beach, the American Cemetery is a solemn site. I was overcome looking at the green fields filled with seemingly endless ranks of crosses and Stars of David, especially when I learned that they represent only a small fraction of the Americans who died here.

Nearby, Overlord Museum offers a comprehensive overview of the entire operation, including exhibits of the vehicles and equipment used by all nationalities. It was here that I learned about the vital role that weapon design played in the war — German panzers required enormous effort (and a crane) to repair, while American and British tanks were easy to fix in the field.

At Sainte-Mère-Église, near Utah Beach, the Airborne Museum documents one of the invasion’s earliest missions. In the dark of night, hours before the bulk of the forces landed, paratroopers jumped in from so-called ‘flying coffins,’ unpowered wood-and-canvas gliders that packed 30 soldiers into their cramped, unlit bellies.

It was a deadly descent — some were caught in fires that gripped the town and others had their chutes tangled in trees or, in the case of paratrooper John Steele, on a church spire. (You can see an effigy of Private Steel and his parachute hanging from the church as a memorial.)

The highest point between Utah and Omaha is a promontory, Pointe-du-Hoc, which is still littered with craters from Allied shelling and the bombed-out remnants of German bunkers. Looking down the sheer 30 m (100 ft) cliff, it’s easy to understand why one naval officer declared the mission to take Pointe-du-Hoc simply impossible: ‘Three old women with brooms could keep the Rangers from climbing those cliffs’. Nonetheless, the US Army Ranger Assault Group scaled the cliff under heavy fire and managed to seize the bunkers.

Gold and Sword

East of the American battlefields, the British landed at Gold and Sword beaches.

The battle plan necessitated an enormous influx of heavy equipment in the very early days, and the Allies couldn’t afford to wait until the deep-water ports were captured. Instead, they created a Mulberry Harbour, an artificial port in the waters off Arromanches (codename: Gold).

At low tide, you can still see the remnants in the distance, massive concrete-slab-like ruins jutting up from the water. Nearby, Musée du débarquement (Landing Museum) includes exhibits that display working models of the mulberries as well as rare news footage from the BBC correspondents who filmed (and died) here.

Many of the German dead — more than 20,000 of them — are buried at nearby La Cambe, often called the German Cemetery. The grounds are meticulously manicured and dotted with leafy trees, but the markers are small and flush to the ground. Rows are divided by broken lines of massive crosses, roughly hewn from dark stone.

By contrast, Ranville War Cemetery is filled with regiments of tall white headstones that gleam in the irregular sunlight. It’s the final resting place of more than 2,000 predominantly British soldiers, including Lieutenant Brotheridge, the first Allied soldier to die in the battle.

Brotheridge was lost at Pegasus Bridge, a tactical linchpin that offered access to Caen, a relatively open area where troops could operate more easily than in the dense bocage (hedgerow) terrain to the west. Capturing the city and surrounding countryside would both inhibit German movements and provide locations for the Allies to build airstrips.

Hours before even the incursion at Sainte-Mère-Église, British RAF troops slipped in under the cover of darkness on gliders to take the bridge. You can visit the original structure and see the bullet holes from the battle and the places where the Nazi soldiers had hung dynamite in a vain attempt to destroy the bridge in case of ambush.

There’s also a reproduction of one of the Horsa gliders (the originals were mostly burned as firewood). It’s remarkable to see these flimsy gliders and realize how much of the battle hinged them and the men inside.

At Ouistreham, you can explore the Grand Bunker, a brutalist hulk of concrete where the Nazis had their communications and control operations, as well as a bunk room and infirmary. Nearby, the Merville Battery preserves four Nazi casemates, fortified cement shelters known as pillboxes that are literally dug into the earth. You can also see a rare surviving Douglas C-47 Transport Plane, which was used to drop 17 paratroopers onto Utah Beach during the battle.

Juno

Located between Sword and Gold, Juno is the Canadian beachhead that played a key role in the battle, which you can explore farther at the Juno Beach Centre. Run largely by Canadian volunteers, this museum covers not just the invasion but also the civilian war effort.

A 30-minute drive from the beach, you’ll find the Château d'Audrieu. This 11th century manor was originally a gift from William, Duke of Normandy and King of England, to his cook after the Battle of Hastings. Legend has it that the cook was ennobled as a reward for valorous combat with a kitchen strainer.

Nine centuries later, the Nazis seized the building for a headquarters. Today, it’s a sumptuous hotel, with a gourmet restaurant and a suite set high in the branches of a tree that overlooks the Renaissance-style gardens. Now an elegant and airy treehouse, it was originally a Nazi lookout during the occupation.

Closer to the city of Caen, Abbey d'Ardenne was the headquarters of the local SS Panzer Division. This peaceful abbey, surrounded by gardens, was the site of a brutal massacre — 20 Canadian soldiers were summarily executed in the wake of the invasion.

Though it’s near the Canadian beachhead, the Château de Creully was the tactical HQ for Britain’s Field Marshal Montgomery and BBC war correspondents. The Canadian RAF built the Allies’ first airfield here on the sweeping plains that overlook the beaches.

What to eat in Normandy

Normandy’s cool coastal climate and gently hilly terrain lend themselves to a different culinary palette than you find elsewhere in France.

Here, the customary French vineyards give way to rolling pastureland covered in neat rows of gnarled apple trees. Norman orchards produce about 800 varieties of apples, most of them astringent, bitter or mealy when eaten out of hand. However, when pressed and fermented, they create ciders that are as complex and subtle as wines.

This is also the home of Calvados, the apple brandy named after the area in central Normandy. Calvados is an AOC appellation — only producers using approved traditional methods from certain areas can claim the name. Double-distilled in copper stills, it’s aged in oak barrels, creating a silky, amber-hued spirit with notes of honey and hazelnuts.

On the region’s grassy meadows cows glut themselves, producing rich milk that makes exquisite cheeses. The best known is the AOC-protected Camembert de Normandie, a lush, creamy soft cheese with a salty, buttery taste that pairs well with Calvados.

And, of course, the long, fertile coast offers impeccably fresh seafood. The best meal I’ve ever had in France was a simple plate of mussels steamed in cider from in a seaside café in Honfleur. As is traditional, I used one mussel’s shell as pincers to pluck the golden-orange meat from the others. Bursting with sweetness, the morsel was delicate, tender and almost creamy, with the hint of apples lingering on my tongue.

Start planning your trip to Normandy

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in France