By India specialist Andy

India packs quite the punch, and arguably nowhere more so than the western foothills. On one trip here you can visit one of India’s greatest Sikh temples, an exiled Tibetan community and a city built on holy Hindu sites. The scenery veers from villages that cling to hillsides like clams, to flower-filled Punjabi meadows. And the architecture? Mock-Tudor Britishisms sit alongside neo-Gothic churches, Hindu temples and Buddhist shrines.

The journey is part of the adventure here. Sometimes, the best experience comes from a cup of chai at a little-visited train station, or a roadside stop that leads to an offering-filled temple. The extensive rail network won’t speed up your trip, but it’s likely to make travel more interesting.

There are many ways you can put a trip together in this region, but my recommendations are based on a recent trip where I combined rail with some scenic drives facilitated by Vishal, my ever-smiling driver.

Shimla

Since tenacious British railway engineers carved out 107 tunnels and built 864 bridges to open the Kalka-Shimla railway, the summer capital of the British Raj has been the gateway to the western Himalaya. From Delhi, you can catch an ordinary express train north to Kalka, before connecting with the narrow-gauge railway and its fondly nicknamed toy trains.

You feel your ears pop as the train zigzags upward to Shimla at 2,276 m (7,467 ft). I first came to Shimla as a backpacker more than 20 years ago, and in the years since it has bloomed across the hillside into a veritable mountain-city. But, its British-colonial core is very much intact (and the monkeys are just as badly behaved).

You can wander the pedestrian Mall Road, which exhibits a surreal mix of British architectural styles. The mock-Tudor Barnes Court stands close to the neo-Gothic Gaiety Theatre and a selection of Renaissance-style, slate-roofed mansions. Stay for a few nights at Clarkes, one of the town’s oldest hotels, and you’re right in the midst of things.

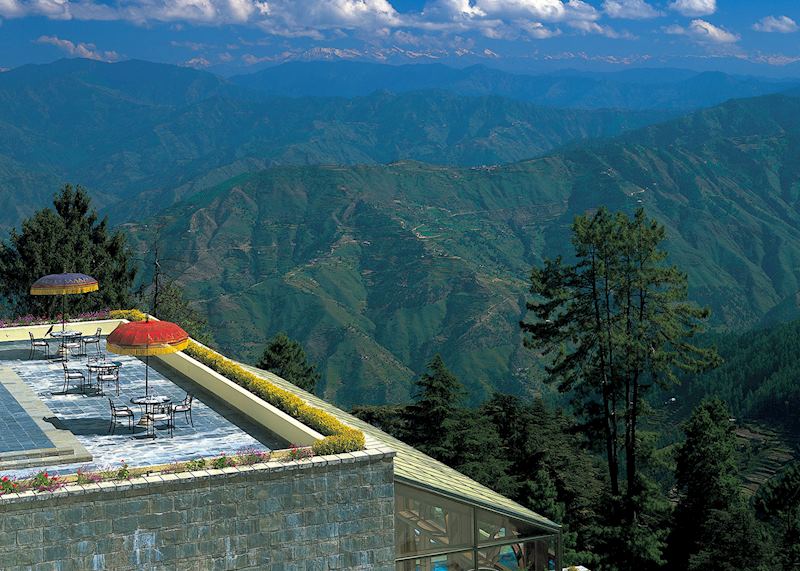

Shimla’s mountainside location is a big draw, but it can be difficult to appreciate from the middle of town. Overlooking Shimla is Wildflower Hall, now a luxury hotel but once owned by Lord Kitchener, Commander in Chief of India until 1911. You can visit the castle-like retreat for afternoon tea and a soak in the heated alfresco pool with views across the snow-tipped Himalaya. Pair it with a stay in Clarkes for the best of both worlds.

The thick cedar forest around Wildflower Hall is lined with walking trails. Some veer upward on day-long hikes, others take you on a leisurely meander through the trees. With my local guide, I followed the romantically named Sleeping Beauty Trail, which loops Elysium Hill.

Passing roasted-peanut sellers and children on their way to school, we circled down toward Shimla through the residential outskirts. My guide drummed up a potted history of each colonial-era mansion we passed, including Mrs Montague’s wooden-fronted property (she was the last British colonialist to be born, live and die in the city). You also pass some abandoned (deemed haunted) stone-dressed manors, left looking like period film sets.

Shimla to Dharamshala

Shimla and Dharamshala, home to the Dalai Lama and a community of exiled Tibetans, both rank high on a trip through the Indian Himalaya, but the journey between them is as much of a highlight for me.

From Shimla, it’s a six-hour drive along the spruce-lined roads that coil around the hillsides to the town of Garli. On a clear day, you can see to the snowline of the higher Himalaya. Most visitors bypass the town on an arduous day’s drive up to Dharamshala, but I suggest staying a night here.

Garli rarely gets a guidebook mention, despite its pedigree. It was created as a trading outpost by the Soods, a prosperous Rajasthani merchant clan. The Chateau Garli, a 1920s ode to British architecture, has been converted to a hotel by the descendants of its builder, Lala Mela Ram Sud. The building may have a colonial brick design but the interior design is Rajasthani, which you can see in the embroidered fabrics and stained glass.

I took a walk with one of the hotel team, who showed me the local architecture — a treasure trove of oddities. Predominantly timber traders, the Soods built their homes in an array of styles and you’ll spot anything from faux medieval castles to Portuguese tiled façades, Islamic domes and Italian-inspired villas.

To complete the journey up to Dharamshala, you drive for about two hours to Kangra Station (the most direct route is by car but the train ride is worth a detour). The little country station has a ticket office decked with hand-painted signs, including riding on the roof is not permitted in a slightly shaky hand. A petite woman stood sentinel over her steaming chai stall. I bought a cup, and she waved her hand dismissively at the price list drawn on the wall alongside; it hadn’t been updated for years.

Two trains a day trundle along the line, taking about an hour to reach Paror, another tiny hill station. As the train skirts the foothills, you’ll negotiate steep-sided valleys, passing the Beas River and freshly painted white temples. This is a local train with simple leather seats and glassless windows. It’s a chance to sit alongside Kangra Valley residents with the wind in your hair. From Paror, it’s about an hour’s drive to Dharamshala.

Dharamshala and McLeod Ganj

The hill town of Dharamshala stretches out in an awkward collection of hamlets, dictated by the sharp slopes of the Dhauladhar range and linked by steep roads. The upper region is McLeod Ganj, and it’s what the Dalai Lama and hundreds of exiled Tibetans now call home.

At first glance, McLeod Ganj looks like any other mountain village. Its narrow streets are lined with stalls, fruit sellers and tiny plastic-table-and-chairs cafés. On closer inspection, the stalls sell amber-gold Tibetan prayer bowls, turquoise jewelry and hand-knitted socks and mittens (if you’re going to buy something, I suggest the socks — they last for years). The cafés cook up momos (moist round dumplings filled with vegetables), which have a distinctive twist on top to seal the dough.

As long as you’re comfortable with steep inclines, the best way to explore is on foot with a guide. The focal point is the Tsuglagkhang Temple, known locally as the Dalai Lama Temple for its proximity to his home. You’re welcomed inside, where the walls are painted with intricate mandalas and scarlet-robed monks often sit chanting as Buddhists perform prostrations in front.

My guide insisted I use the temple toilet — they have a wonderful view across the mountains to the town below. The complex also houses a museum illustrating how many Tibetans escaped their country during the Chinese invasion.

You follow a circular route around the temple, which is flanked with prayer wheels to spin as you walk. The wheels should be spun clockwise, which is believed to release the mantra (prayer) held inside. So many prayer flags are tied between the trees, they create vibrant walls that flicker in the wind.

Farther down the hillside is the Norbulingka Institute, which was set up to preserve Tibetan arts and culture. Around a courtyard of cedar trees is a set of workshops, a café and a shop, built in a classic Tibetan style with flat roofs trimmed with red and gold.

One studio clanged with the sound of men hammering the shiny metal top of a chorten (temple) into shape. In another, a silent line of painters sat at canvases stretched across wooden frames.

Dasal, who has been creating artwork here for more than 18 years, stood up to greet me, carefully raising his thangka to show me. Thangkas are intricate paintings on silk that use hand-ground mineral pigments. Traditionally used as meditation aids, they usually depict a deity or Buddhist master. The detail in the examples I saw was so fine I had to squint to make it out.

Where to stay in McLeod Ganj

Chonor House is right in the main town. Each of the hotel’s rooms is decorated with hand-knotted fabrics, carved wooden furniture and paintings from the Norbulingka Institute. A couple of nights in Dharamshala are enough for you to see the sights, but the surrounding hills are laced with walking trails if you’d like to linger here.

Dharamshala to Amritsar

From the foothills of the Himalaya, the roads coil downward to the flat plains of the Punjab. Cedar and pine forests become sparse, making room for fields of corn and maize. You could drive between Dharamshala and Amritsar in about six hours — although a stubborn cow or sluggish bus can make it longer — or spend the night in the Punjab en route. I stayed at Punjabiyat Lodge, a series of newly built cottages set on a farm surrounded by rapeseed fields.

Amritsar

In all my visits to India, I’ve never seen anything like Amritsar’s Golden Temple — for me, it beats the Taj Mahal. My first sight of it was at night, when the water surrounding it glows with the reflection of the gilded shrine. Worshipers queue along a narrow causeway strung with lights to enter the sanctum sanctorum, the inner shrine, to pray to Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh scripture).

The golden shrine is part of a larger complex, known to Sikhs as Harmandir Sahib. The sarovar (pool of nectar) that encircles the shrine is the focus for many, who bathe in its holy waters. Many pilgrims stay in dormitories on-site, fed by a huge open-air kitchen.

You’re welcome to volunteer in the kitchen and, in turn, sit to enjoy a meal. ‘Make rounder, make rounder.’ A commanding woman inspected my attempts at rolling out chapati dough as I sat around a large table with 20 or so other volunteers. I then sat, covered in flour, and ate my share of dhal and rice (with a perfectly spherical chapati).

You can also wash up or serve food as part of the slick operation that serves more than 100,000 people daily.

Across the road from the temple is Jallianwala Bagh, a walled public garden. In 1919, British Army troops under the command of Colonel Dyer fired on a crowd of pilgrims who’d gathered there to celebrate Baisakhi, a Punjabi festival (as depicted in the 1982 film Gandhi).

The garden is now a memorial to the hundreds of people who were killed, the bullet holes still present on the walls. Many signs are in English, but my local guide explained how the massacre unfolded in more detail.

About an hour’s drive from Amritsar is Wagah, a border town that straddles India and Pakistan. Each evening, the border closes in an elaborate ceremony as squads of soldiers attempt to flaunt the most dramatic postures and gestures.

About 20 years ago, I watched this spectacle from the Pakistani side, among a few rows of visitors. Now, there’s tiered seating on either side, and the crowds shout encouragement — the man sat next to me had journeyed from Calcutta to take part.

You can see Amritsar’s sights in a day with the help of a driver and local guide. The Ramada Amritsar hotel (decorated with the glitz of a Bollywood film set) is around the corner from the Golden Temple and convenient for an evening visit.

Haridwar

From Amritsar, a train line skirts along the foothills, eventually arriving at the city of Haridwar. It marks the point where the Ganges runs down from the Himalaya onto the Indian plains. On the eight-hour train ride, you pass through three Indian states and are offered copious cups of rail-side chai.

For Hindus, Varanasi is the city of death, and Haridwar the city of birth, its history intertwined with the origins of Hinduism. Pilgrims come to the ghats (sacred steps that lead into the water), to bathe in the water which is believed to have purifying properties.

By day, you can wander between temples, intricately carved havelis (mansions) and vibrant statues of Hindu gods and goddesses. Markets sell stone idols, rudraksha (Hindu prayer beads) and piles of kumkuma, the powder for dotting the forehead.

In the evening, the riverbanks become thick with people preparing their offerings for the evening aarti ceremony. As I waited, one of the barbers who line the streets (some devotees shave their heads before the ceremony) gave me the best cut-throat shave I’ve ever had.

Sitting on some steps, squeezed in-between a family who kept offering me sweets and an elderly couple with their hands clasped together, I noticed the fragrance of incense in the air. The ceremony starts with the ringing of bells, as hands are raised to the heavens. A thousand voices begin to chant as the pundits (priests) light fire bowls, holding them above the crowds. Brass and gold trays are set on the water and begin to float down the river, filled with offerings or flowers, food and glittering oil lamps.

The hotels in Haridwar are simple and don’t serve meat or alcohol on religious grounds. The Haveli Hari Ganga is 20 minutes’ walk from the evening aarti ceremony and its restaurant makes a particularly good badam (a warm milk concoction of spices, almonds and raisins).

From Haridwar, it’s a days train journey back to Delhi, where you can catch your international flight home.

Read more about trips to India

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in India