By Italy specialist Caroline

Like most, I first experienced Italian culture years before setting foot in the country, through its cuisine. After moving to Bologna and traversing the country from top to bottom, it became clear that its success lies in its emphasis on locally grown, fresh ingredients. This tradition of using whatever produce is in season, plus a proud sense of regional identity, has led to characteristic dishes wherever you travel.

Pasta, pizza, carne (meat) and pesce (fish) are the standard fixtures on restaurant menus up and down Italy. In this guide, I focus on Italy’s more renowned culinary cities and regions, and single out a few of their speciality food and drink offerings. In some instances, you can have the added experience of making (or catching) your food, using long-established methods, before you sit down to dine.

What to eat and drink in Italy: my selected food highlights

As a general rule, for more genuine, tastier versions of ubiquitous dishes such as pizza or spaghetti carbonara, order them in their places of origin. Here, it’s likely they’ll be prepared to exacting standards, using age-old recipes.

Cicchetti in Venice

In the maze of streets around Venice’s central San Polo district you’ll see modest bars that are little more than holes in the wall. Groups of local people congregate outside around tables made out of old wine barrels.

Around lunchtime, and again at early evening, these bars (called bacari in the Venetian dialect), serve Venice’s version of tapas. When in Venice, however, don’t refer to these light dishes as ‘tapas’, as Venetians dislike the term — they call them ‘cicchetti’. You’ll snack on, say, crostini with a seafood or meat topping, while sipping a Veneto wine.

One place right by the Rialto Bridge puts out a big bowl of focaccia and serves prosecco with strawberry purée as the house drink. Other typical Venetian drinks include the classic bellini (prosecco with fresh white peach purée) and the aperol spritz.

Stand at the bar like the locals or perch on a wall by a canal. You’ll find many good bacari on the Zattere (a waterfront promenade) in southwest Venice.

- Read our guide to the Secret canals and corners of Venice

Tiramisú

You’ll find tiramisú on most Italian menus, but its true home is Venice. Like many Italian dishes, it’s deceptively simple: long, thin sponges (called ‘ladyfingers’) are soaked in espresso and served with a whipped-up topping of mascarpone cheese, eggs and sugar. Every family in Italy will adapt the standard recipe to suit their tastes, like replacing the espresso with marsala wine.

Try a wine tasting with lunch in Tuscany

Sitting amid gently sloping valleys, the manicured rows of vines on the Fèlsina Estate produce the dry red wines that Tuscany’s Chianti region is known for worldwide.

The tasting experience begins with a drive to the top of the vineyards, where you can walk among the vines (eating grapes straight off them as you go, depending on the time of year) and learn about the area’s viticulture. As you look back across to the estate buildings, you might glimpse the vineyard owner making her daily walk up the cypress-lined driveway. (Even in her 90s she remains extremely involved in the family business.)

After seeing how the grapes are dried and stored in the estate’s farmhouse and cellars, the tasting begins. You’ll try both newer and richer, more mature wines, and learn how the area’s weather and soil conditions have contributed to producing the vintages. The rooster on the wine labels is the symbol of an authentic Chianti wine.

Then you’ll be taken to nearby Castello di Meleto, an 11th-century privately owned castle, for lunch in its herb gardens. Each course (consisting of, for example, local salami and cheeses) is paired with a different Chianti wine.

When I visited, I made a surprise discovery. I’ve never been a fan of dessert wine, but the variety served in Tuscany was great — not too sugary at all. It was especially delicious when we followed the local tradition of dipping biscotti (biscuits) into it.

Make pasta by hand in Tuscany

Of all the pasta-making classes I’ve tried in Italy, the one in the kitchens of Castello di Meleto stands out.

The instructor was refreshingly hands-on yet patient as she planted me in front of a big pile of flour, showing me how to make a hollow in the middle of it for the eggs and then slowly mix it all until you form a ball of dough. Using a huge rolling pin, you then roll it out until it’s extremely thin — a process that’s much harder than it looks and took me over 25 minutes to get right.

Then she showed me how to sculpt different pasta shapes by hand, from Tuscany’s traditional pappardelle (broad ribbons) to tortellini (known as ‘hats’) and farfalle (bows). It’s an art form.

After the class, I was able to eat my freshly made handiwork in different sauces prepared by the castle’s chef. One was a rich ragù using pork procured from the castle’s resident Cinta pigs. The other was one of those humble yet scrumptious classic Italian sauces made out of as little as three ingredients: fresh tomatoes, basil and salt.

Rome’s pasta

I have a real weakness for a pasta dish that originated in Rome. Cacio e pepe (‘cheese and pepper’) is a dazzlingly simple concoction made with vermicelli, black pepper and lashings of grated pecorino. Try it in a backstreet trattoria in Rome’s down-to-earth Trastevere district, where you might find it served in a cone of cheese. Another pasta plate native to Rome (and best eaten in Trastevere) is creamy, pancetta-strewn spaghetti carbonara.

Street food in Naples

If you’re looking for a quick lunch snack on the go in Naples, wander around the old town or near the waterfront. You’ll be drawn by the smell of frying to little stalls or booths lining the streets: see which ones seem popular with local Neapolitans before sampling their fare.

Top of my list is pizza fritta, a twist on the city’s most famous culinary invention, pizza. A circle of dough is stuffed with cheese then closed up, like a calzone, and fried. You eat it straight away, cupped in grease-proof paper. I also like the fried balls of macaroni you’ll see street vendors selling.

For something sweeter, from Neapolitan pasticcerias (cake and pastry shops), you can buy shell-shaped sfogliatelle pastries, or small cakes called babas. They’re soaked in rum and sprinkled with powdered sugar.

Authentic pizza in Naples

Pizza being my all-time preferred food, going to Naples is something of a pilgrimage for me. Not just any pizza, though — my pick is the staunchly traditional Neapolitan-born pizza margherita, named after Italy’s 19th-century queen consort.

It’s simply mozzarella or fuore di latte cheese, basil, and tomato sauce spread on a dough base so thin that it cooks in 90 seconds. (‘Deep pan’ varieties don’t exist here.) Some chefs like to add their own twist or extra toppings, but most Neapolitans keep it simple and classic. Head to the Lungo Mare waterfront for some of the best pizzerias in the city.

Cook with a local family on the Amalfi Coast

On the Amalfi Coast in southern Italy, seafood is the order of the day. For seafood aficionados, I highly recommend this class run in the home of Laura D’Antonio with her son Fabrizio, to whom she’s passed on her training in Michelin-standard cuisine. In the kitchen of their home in the hilltop village of Sant’Agata, I focused on how to prepare and de-bone fish in order to make acqua pazza (literally meaning ‘crazy water’). This poached white fish dish is cooked in olives, capers, tomatoes and wine.

First, though, we prepared antipasti. It was at this point that Fabrizio dispelled one of my existing food prejudices. We were making anchovy skewers with bread, tomato and basil, when I informed him I didn’t care much for anchovies. 'Trust me,' he said, and urged me to try one. They were much bigger and far less salty than others I’ve eaten — in fact, they didn’t taste fishy at all, and I can honestly say I loved this dish.

Catch your own dinner in Sorrento

A wide, paved stairway zigzagging down from the old town through a jumble of painted residences brings you to Sorrento’s Marina Grande. There, you’ll meet local fisherman and restauranteur, Gaetano. He’ll take you out into the bay to the spot where he cast his nets earlier in the day. At 800 m (2,625 ft) long, they take over 30 minutes to haul in.

You’re then invited to help cast the nets yourself and pull them back up. It’s strenuous work, but exciting when you begin to see the fruits of your toil ensnared in the netting — including the odd starfish or sea cucumber. Everything you have caught is gathered into a bucket before you journey back to the marina. En route, you can stop off to swim in a sea grotto frequented by locals.

Back in port, your catch is cooked at Gaetano's restaurant, O’Puledrone, in two batches. In one, everything is fried whole in a light batter and you’re shown how to eat the various fish by splitting them open and pulling out the bones in one go. The rest of your catch is grilled.

If you aren’t used to eating fish whole and not filleted, you’ll need to be adventurous and open-minded. But it’s the freshest catch you’re ever likely to try, and the setting — outside on the terrace with a sea view as the sun sets — makes it a relaxing end to an energetic afternoon.

You may also like to try the Amalfi Coast’s local drink, limoncello. A liqueur made with the region's lemons, it’s often served as a free digestive. For dessert, I would recommend Torta Caprese. Originating on the island of Capri just off the Amalfi Coast, this is a rich, dense cake made with almonds and chocolate, and dusted with powdered sugar.

A note on gelato

The gelatería is a national institution in Italy with a presence in even the smallest village square. The gelato these establishments sell (and for the most part make on the premises) isn’t exactly ice-cream. It has less fat than ice-cream, is churned more slowly, and is served at a higher temperature, making it silkier. At a gelatería, don’t hesitate to make like the locals and ask to sample several varieties before making your final selection.

Sampling street food in Palermo, Sicily

I was trying arancini, one of the island’s best-known street foods. The crispy shell broke open under my teeth, revealing a creamy interior of saffron-yellow risotto streaked with a smear of deep-rusty orange, the first hints of the beef filling. A wisp of steam curled up into the cool spring air.

My guide, Giorgio, watched me with a proud smile. As a Palermo native, he seemed to take a special home-town pride in what’s arguably Sicily’s signature dish. The fried rice balls were just the first taste on a walking (and eating) tour of the street food available in Palermo.

The city’s daily market is a noisy, crowded place. Sellers hawk their wares in rising and falling sing-song chants, people haggle passionately over their purchases, and giant vats of hot oil spit and hiss as the cooks at the friggitorie (frying stalls) lower fresh fish into the boiling cauldrons.

Many of the dishes you can try might be familiar. There’s sfincione, a thick and chewy pizza-like bread. Ricotta salata is a dry, crumbly cheese created by pressing the more familiar fresh ricotta. Other delicacies include cannoli, crispy shells filled with sweetened ricotta, and granita, shaved ice doused with lemon or coffee syrup.

Some dishes, however, resist widespread recognition — pani ca meusa, for example. This grease-bomb of a sandwich is made of cooked spleen and lung, mixed with rendered lard and served on a soft bun. The intense, rich filling is served with a splash of lemon, to heighten the taste, or a bit of cheese to tone it down, depending on your personal tastes. (I admit that I tried it with cheese).

Gastronomic tour of Emilia-Romagna

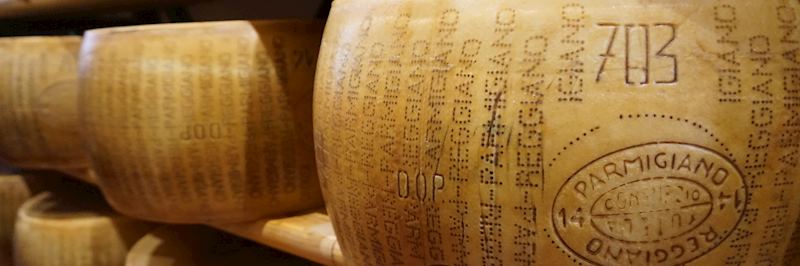

Known as the culinary heart of Italy, Emilia-Romagna is the home of many of Italy’s renowned foods: Parmigiano Reggiano cheese, aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena (balsamic vinegar) and prosciutto di Parma.

These foods have been prepared in the same way in the same region for hundreds or even thousands of years, and you can take a tasting tour with three of the artisanal producers who still flourish in Emilia-Romagna’s countryside.

Your first stop is to a Parmigiano Reggiano producer, where workers in knee-high rubber boots pour huge buckets of milk into gleaming copper vats. After the milk was heated and stirred, I watched them cut the curds with long, straight metal spatulas and press the soft white mass into wooden forms. The wheels of cheese were then pressed, cooled, brined and washed.

But making the cheese is just the first part of the process. The workers move the wheels onto towering rows of shelves to age slowly. My host explained how the cheeses are washed by an automatic machine and how the casaro (cheesemaker) taps each wheel with a small hammer to hear how well it’s faring.

The next stop is a stone manor house in the Modena countryside. When you walk into the room where the vinegar is aged, you first notice the smell — eye-wateringly sharp, it hits you like a slap in the face.

The vinegar is made from cooked must — the remnants of pressed grapes — and then gradually decanted in a series of smaller and smaller casks made of different woods, which are left open to allow for evaporation.

In the tasting room, I tried several different ages, from a relatively young 12-year-old to a remarkable 25-year-old. Those acidic, sugary supermarket versions are entirely unrelated to these nuanced condiments — mellow, sweet and viscous, they were layered with smoky hints of oak and chestnut woods.

Finally, you visit a prosciutteria, where prosciutto di Parma is aged. My host introduced me to the free-range pigs: fast-moving, black-skinned animals from an ancient local breed called nero di Parma. Then he escorted me into the curing room, where ranks of salted hams slowly dried in the carefully controlled environment.

In the tasting room, you get to sample slices of the ham. Cut so thin that the sun shines through the rosy pink meat, the slices are ringed with a narrow border of meltingly rich fat. Salty, earthy, with a lingering complexity, the prosciutto was simply delicious.

Eat like an Italian

Food is a cornerstone of the Italian lifestyle. Meals are long and lingered over; culinary traditions are lovingly upheld and celebrated.

When it comes to eating out, you have several options. A ristorante generally offers more formal dining with table linen, whereas a trattoria is more of a family-run eatery that serves local or regional dishes. An osteria is similarly informal, and they often have a rustic feel.

Breakfast in Italy is traditionally a small meal — perhaps just a cappuccino (which Italians never drink after 10am) and a pastry such as a cornetto (croissant). Lunch is the main event. It’s the culinary highlight of the day — especially on Sundays, when families customarily gather for meals that can last for hours.

Aperitivi (pre-dinner drinks and accompanying snacks, such as nuts or olives) is an institution, and one of the Italian dining traditions I most enjoy. Some bars will offer a buffet of small snacks to try alongside your drink. Dinner is eaten late: in Italian cities, you’ll notice that some restaurants are at their busiest around 10pm.

Italians also prize eating seasonally. On my last trip to Venice, asparagus — grown in the market gardens of some lagoon islands — was in season, so it was part of almost every meal I ate. Some restaurants will refuse to serve ingredients that are out of season, and menus adapt throughout the year. It was also here, in Italy, that the Slow Food movement was founded, its ethos being environmentally responsible, naturally produced food.

A word on coffee: it’s customary in Italy to drink it standing up at a bar, especially in urban areas. Ironically, Italians also seem to have mastered the art of nursing a coffee outside on a terrace, whatever the weather.

Plan your culinary experience in Italy

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Italy