‘Himalaya’ translates from Sanskrit as ‘land of snow’, and its white arc of peaks is visible from space. This geological giant sweeps from the Pakistan-India border, past Nepalese peaks, Bhutanese villages and the Tibetan Plateau, to taper down into China’s Yunnan province.

A visit to this region doesn’t have to mean days of trekking. Below the snowline, you can ride mountain railways in India, spot rhinos in Nepal or traverse the Friendship Highway through Tibet. You can’t fit all this into one trip, so our specialists have summed up each country to help you choose.

Nepal

By Amber

Because the world’s highest peaks cluster mainly in Nepal, the country is most synonymous with the term Himalaya. Its calling card is a mountainscape of snow-crowned peaks, but they don’t exist in a vacuum. You’ll find a culture, a belief system and wildlife that has developed within the steep-sided valleys below.

For me, Nepal’s draw is the variety of experiences you can fit into a two-week trip. You’ll start in Kathmandu’s old town, where medieval temples, palaces and Buddhist monasteries vie for attention amid vegetable markets and craft bazaars.

From the capital, you might travel onto Bhaktapur, Nepal’s best-preserved medieval city, or the village of Bandipur, whose streets are lined with traditional wooden Mawari mansions.

To the south, you can explore Chitwan National Park’s river plains and jungle by 4x4 or dugout canoe. In the grasslands you’re likely to see one-horned rhinos and elephants, while the subtropical forests shelter vultures, eagles and a long list of elusive mammals, including the Bengal tiger.

As for the mountains themselves, you have a choice of treks or, if you just want to admire the view, a scenic Everest flight from Kathmandu.

Tibet’s Friendship Highway

By Duncan

If you’re seeking adventure — that doesn’t necessarily involve intense physical activity — the Tibetan Himalaya calls. Places to stay are basic (there’s the occasional outdoor drop toilet), but in return you’ll experience one of the Himalaya’s remotest areas and some of the best mountain views in the world.

You don’t have to deliberate about where to go. The Friendship Highway, which runs from Lhasa in Tibet to Kathmandu, is the only real route to follow. You’ll need around two and a half weeks, accompanied by a driver and guide.

Most of Tibet’s towns and villages are interspersed along the highway at an altitude of around 3,500 m (11,500 ft). As you move along the road, passing the second-largest city of Shigatse, the Himalaya really come into view.

The scenery becomes stark and barren as the Himalaya massif looms closer. When Everest finally appears ahead of you, there’s no mistaking its triangular shape dominating the horizon.

You’ll overnight at the highest monastery in the world, Rombuk. The north face of Everest looms large from your bedroom window, and in the evening everyone gathers to watch the sun set over the range.

From here you could take a slight detour to Everest Base Camp. Unlike its Nepali counterpart (yes, there are two), you can reach it by car.

China’s Yunnan province

By Duncan

If you’re tempted by Tibet but it feels a little too off-piste, China’s Yunnan province is a good alternative, where prayer wheels, Buddhist monasteries and Tibetan-speaking villages give you a feel for life in the Tibetan Himalaya proper.

China and India’s foothills bookend the east and west of the Himalaya respectively, but the geography in the Yunnan is more extreme. Tiger Leaping Gorge is one of the deepest ravines in the world, forcing its way through the surprisingly green Haba Mountains. There’s a viewing platform, if you’re driving nearby, but you’ll need to complete a two-day trek to do it justice.

Farther north is Shangri-La, (residents believe it was the inspiration for James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon). From here, you can visit Songzanlin, the largest Tibetan Buddhist monastery in China outside of Tibet, and luxuriate in some high-class hotels, including the Banyan Tree Ringha.

If you’d like to hike, continue to Tacheng, a small village of black-roofed farmhouses, where semi-wild boar roam and some of the oldest trees in the world grow.

Yunnan combines well with Sichuan province (of panda research station fame) for a two-week trip across western China.

The Indian Himalaya

By Andy

Sikkim and West Bengal

Squeezed between Nepal and Bhutan is a thumb-shaped section of the Indian Himalaya. Once the independent Kingdom of Sikkim, it became part of India in 1975 but retained a distinct personality. You can visit the region’s Buddhist monasteries and hike to rarely visited villages along steep valleys brightened by rhododendron groves.

Gangtok, the kingdom’s capital, is where you’ll find Chogyal Palace, the former royal residence, as well as a pedestrians-only high street of tiny eateries.

Pelling is the (village-like) second city, overlooked by the sheer walls of Kangchenjunga, the world’s third-highest mountain. On a clear day, you can see across to Everest (which, from this angle, looks small by comparison).

On a two-week trip across the region, you can cross the southern Sikkimese border into the narrow band of West Bengal that sweeps north above Bangladesh. Darjeeling, a former British hill station, is set to a backdrop of forested hills and tea plantations. Unlike Shimla, the town has shaken off its colonial beginnings and is a hub for Nepalese, Tibetan and West Bengali people — visit the nightly market to peruse goods from across the subcontinent.

You can take a scenic ride on the Darjeeling Mountain Railway to the nearby town of Ghoom, where Tenzing Norgay’s Himalayan Mountaineering Institute houses a museum dedicated to mountain climbing. A sunrise visit to Tiger Hill beforehand will (weather depending) put you face to face with the Everest massif. And, for a little relaxation, spend a few nights on a Himalayan tea estate, such as Glenburn.

The western foothills

By Himalayan standards, it’s not particularly high here, but these rolls of green that ripple out from the harsher peaks give you the most variety over a two-week trip. Every town and village could be a base for a gentle walk, passing through thick evergreen forests and highland meadows with the snow-capped higher Himalaya peeking out above.

Just a few hours north of Delhi is Kalka, the start of the Kalka-Shimla toy trainline, which weaves for 96 km (60 miles) up the Siwalik Hills. You disembark in Shimla, where the 19th-century British colonial government ruled during humid Indian summers. The British influence is still palpable in the hill town’s half-timbered hall and mock-Tudor frontages.

Farther into the hills, the town of Dharamshala clings to a steep ridge like a snowdrift. The upper town, McLeod Ganj, converges around the flickering Tibetan prayer flags of the Tsuglagkhang Complex. This is the Dalai Lama’s home in exile and now an important Buddhist monastery for the red-robed monks you’ll see about town.

The region is also important to the Sikh community, who regularly pilgrimage across the Himalaya to visit Amritsar’s Golden Temple, their most sacred shrine. My initial sighting of its gilded walls, reflected off the surrounding sacred pool, pips when I first saw the Taj Mahal.

Ladakh

Despite its past ties to Tibet, its Nepalese influences and the fact it’s part of India, Ladakh still feels like its own country. Hemmed in by mountains (you fly in via Delhi), it’s a nation that has learned self-sufficiency, and it competes with Bhutan as the most traditional Himalayan region.

Its geography means that the best (and only) time to visit is between June and September, when the mountain passes are clear of snow. Isolation has its benefits — raiding Mughal armies never made it this far and you’ll find some of India’s wealthiest monasteries decorating outcrops and ridges, and poking up from the valley floor.

The Himalaya form a scenic backdrop to some places, but in Ladakh it feels like you’re right up there, surrounded by peaks. Getting around Ladakh requires a lot of driving, but the sweeping roads are a high point in both senses, especially the world’s highest motorable pass, the Khardung La, at 5,380 m (17,650 ft).

Aside from gaping at the scenery, the highlights of Ladakh include streets of mud-brick houses and the jack-of-all-trades market in the capital, Leh. You’ll see some of the world’s rarest Buddhist art in the unassuming village of Alchi, in the guise of 11th-century monastery frescoes. Deeper into the Himalaya is the Nubra Valley, a network of tiny, isolated villages joined by hiking trails.

The tiny mountain kingdom of Bhutan

By Amber

Few people acquire a Bhutan passport stamp, but there’s something very special about this fiercely independent, staunchly traditional country that measures progress by Gross National Happiness.

Bhutan can’t claim the nicest hotels, the most elegant dining options or the best value for money. On the other hand, few places have preserved their culture so successfully — even new buildings must be constructed using traditional architectural methods.

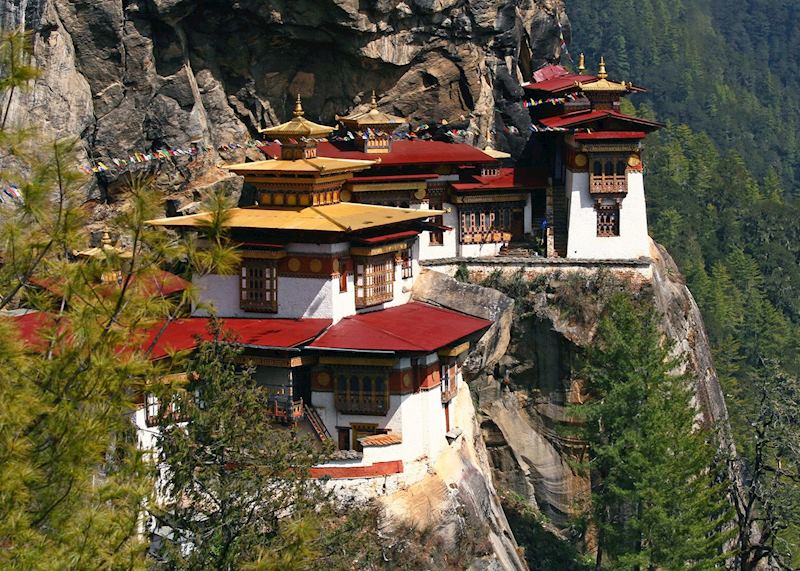

Aside from Tiger’s Nest Monastery, which hangs off a cliff near Paro, you’re not going to cross off a list of must-see sights. Instead, time here is best spent venturing into the countryside, stopping to walk through tiny villages that have bloomed around 17th-century dzongs (fortresses). Plan your trip around a Bhutanese festival to see communities gathered together.

A hike through Bhutanese countryside takes you past landscapes dotted with chortens (shrines), prayer flags and prayer wheels set into the streams and turned by the water. The Druk Path, an old trading route between Paro and Thimphu, winds through quiet forestry trails and yak pastures.

Visit in spring and the valley walls are bright with rhododendrons. And, in the central Phobjikha Valley, you can see where most of Asia’s black-necked cranes over winter.

Read more about trips to the Himalaya

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.