By Morocco specialist Olivia

If you’ve already visited Morocco, it’s likely you visited the classic sights like the souqs of Fez and Marrakesh, the sleepy coastal town of Essaouira or the High Atlas mountains.

But for a return trip, I suggest a tour that lets you delve deeper into the modern side of Marrakesh and then takes you through parts of southern Morocco. Not only will you get a richer insight into the country, you’re also likely to be one of just a few visitors. You can admire centuries-old calligraphy in Tamegroute, see an 800-year-old granary and go shopping at Morocco’s silver capital, as well as visit the fortified caravan town where Game of Thrones was filmed.

Modern Moroccan art in Marrakesh

Morocco has long been a crossroads for empires — a turbulent past that’s left behind a complex and rich artistic legacy. Modern art may not be the first thing you picture when you think of Morocco, but Marrakesh has a thriving contemporary art scene that you can explore on a half-day private tour.

Together with your guide, you’ll set off from the Musée d’Art et de Culture de Marrakech (MACMA), a small private museum set within the city’s modern district of Gueliz. With an evolving collection of contemporary and historic art and photography exhibitions, it’s hard to say what you’ll see, but expect to be taken on an intimate journey through Morocco’s past, present and the intermingling of the two.

From there, you’ll make your way to the Musée de la Palmeraie, a private collection just north of Marrakesh. Abderrazzak Benchaâbane is a botanist and perfumer who collects and displays contemporary African art by local artists in his elegant home, which has been converted into a museum. The garden itself is an artistic feat, lined with an impressive array of cacti in all shapes, sizes, and hues.

The tour concludes at the private museum of Farid Belkahia, a Moroccan artist who was known for using traditional artisan techniques in a contemporary style. Among the works, you’ll notice his shifting influences and expressions, from copperwork inspired by Amazigh culture to leatherwork dyed with natural pigments like henna.

Taroudant, the Godmother of Marrakesh

Located about three hours’ drive south, Taroudant closely resembles Marrakesh, its larger, better-known counterpart. In fact, Taroudant is often called the Godmother of Marrakesh. You’ll find the same red-mud walls and palm-shaded medinas, but with far fewer crowds.

Here, the spice-scented souq is an everyday working market, as opposed to the photo-ready sort that you’ll find in bigger cities. Food stalls are arrayed with fragrant baked sweets, pyramids of dried dates and glistening bowls of olives. Turn the corner and you might stumble on argan oils, cosmetics and beldi, the dark ‘soap’ made from olive oil and olive skins.

Open fields at the market’s edges host woodworkers and livestock pens. This is also where the grain sellers set up shop, scooping barley into cloth sacks and handwoven baskets, their wide shovels kicking up showers of golden grain into the air.

While you’re here, you might like to visit Palais Musée Claudio Bravo, just north of the city — the home and final refuge of Chilean hyperrealist artist Claudio Bravo. He retired here from the busy New York and European art scenes, drawn by the same buoyant, buttery light that’s inspired artists since before Matisse.

His former home-turned-museum spotlights Bravo’s bronze sculptures and paintings, which remind me of Dalí’s work, as well as his wide collection of other artists’ pieces.

Silver and painted rocks in Tiznit and Tafraoute

Two hours' south along the coast, Tiznit sits tucked behind a massive 19th-century earthen fortification. Once a major trading hub, it remains the best place in the country for traditional silverwork. You can find everything from simple pendants to elaborate bridal necklaces strung with huge, filigree pendants and pieces of coral.

Another two hours’ inland will bring you to Tafraoute, a small village surrounded by a Martian-like stonescape of red boulders, granite mountains and, occasionally, painted rocks.

In the 1980s, a European artist named Jean Verame decided to paint some of the stones. You’ll find baby-blue, poison-green and bright-pink boulders nestled among the rust-red ones that litter the landscape. You can spend several hours clambering among them, admiring the views as well as the idiosyncratic tenacity it took to completely cover so many rocks.

You can also spend time (as I did) with an Amazigh family who lives nearby. (The Amazigh are Morocco's indigenous people.) I met Omar, the broad-shouldered patriarch, who sports short hair and a djellaba over a pair of thoroughly Western jeans. His mother dresses more traditionally in a loose black robe trimmed in silver.

When we worked together to make a meal in the house, she wore the robe down, flowing around her waist. But when we stepped outside to meet other women in the village, she swooped it up to wrap around her head and shoulders like a hood, a compromise between modesty and practicality.

An 800-year-old Amazigh granary in Amtoudi

From Tafraoute, I recommend heading south through a stony dry landscape, punctuated by occasional patches of scraggly scrub and scree-sided mountains. After three hours, you arrive at Amtoudi, a small Amazigh village far from anything at all. It’s admittedly a long drive, but worth it, I feel, in order to see the town’s agadir — one of Morocco’s Amazigh granaries.

When I visited (with my driver interpreting), a local man led me up the narrow path that rose in a spiral up the towering precipice to the 11th-century building. The walk was easy to manage, even for my guide, who used a cane, but I could see how it would be very defensible. At the top, we had clear views of the landscape and flat-topped mountains surrounding Amtoudi.

He explained that not only did villagers store their grains here, but it also had space for livestock, honeybee hives, and rooms filled with clay amphorae and cisterns that stored up to three months’ worth of water — enough for the whole village to hold out for a prolonged siege.

Inside the structure, he pointed out bones scribed with faded calligraphy. They were records of the families who lived in the village, updated regularly over the centuries.

An authentic desert experience in Erg Chigaga

An unseasonable sandstorm kicked up as I headed into Erg Chigaga, a swathe of barren desert deep in the heart of the Sahara. The last time I made this journey, the air was thick with sand, dimming the light to a strange, reddish glow, and the road seemed featureless in the swirling chaos. But my driver, Mohamed, navigated with the complete confidence of a man born to the area. Along the way, he explained that he loved his native land, and never wanted to leave.

The sky cleared as we reached Azalai Desert Camp, and I suddenly understood his passion. The desert was wholly empty. Standing on top of a dune, I couldn’t see another soul. Just an ocean of sand, stretching from my feet to the distant, heat-blurred horizon.

The camp itself is unlike the more indulgent options you’ll find in the more well-developed Erg Chebbi. Its white canvas tents are just as elegant, decorated with a sturdy camp table for dining, but you won’t find any running water or air conditioning here.

Instead, I washed off the grit left over from the storm with a solar-heated camp shower, which seemed more respectful of the dry, fragile environment.

Calligraphy and the Quran in Tamegroute

From the depths of the desert, I then suggest heading north along the Draa River Valley, stopping at the small, inconspicuous village of Tamegroute.

It’s easy to bypass this town, which seems like nothing more than a handful of adobe buildings blending seamlessly with the sandy soil. However, it cradles one of the most remarkable libraries on the continent.

Founded in the 17th century, Zawiya Nassiriyya is a prestigious Islamic school and place of religious study. Its adjacent library houses more than 4,000 texts, many of them centuries old.

Safely displayed behind glass, they lie open to pages displaying the elegant calligraphy and precise diagrams created by Islamic scholars. You can pore over texts on algebra, astronomy, mathematics, law and medicine, as well as early copies of the Quran on carefully preserved goat hides.

Some works on display are enormous, with abstract illuminations so elaborate and detailed, they seem fractal. Others were small, just the size of my hand, written in tiny, perfect figures.

Zagora — gateway to Timbuktu

Half an hour’s drive north of Tamegroute, you’ll reach Zagora, a small town that was once the last stop for caravans heading into the sun-blasted nothingness of the Sahara. It was the final place to get water before embarking on a 52-day journey to Timbuktu with no water sources and no reprieve from the endless heat and sand.

Today, Zagora remains an important trading town and hosts a regional souq twice a week as well as several festivals, including an annual international gathering of nomads in April.

The town is surrounded by a palmery, a vast orchard of date trees that’s tended by families who each manage a section. Visit in the autumn, and you might see some of the preparations for harvest — workers easily climbing the trees, using the scales like ladders, so they can hack off inconvenient fronds and check the progress of the fruit.

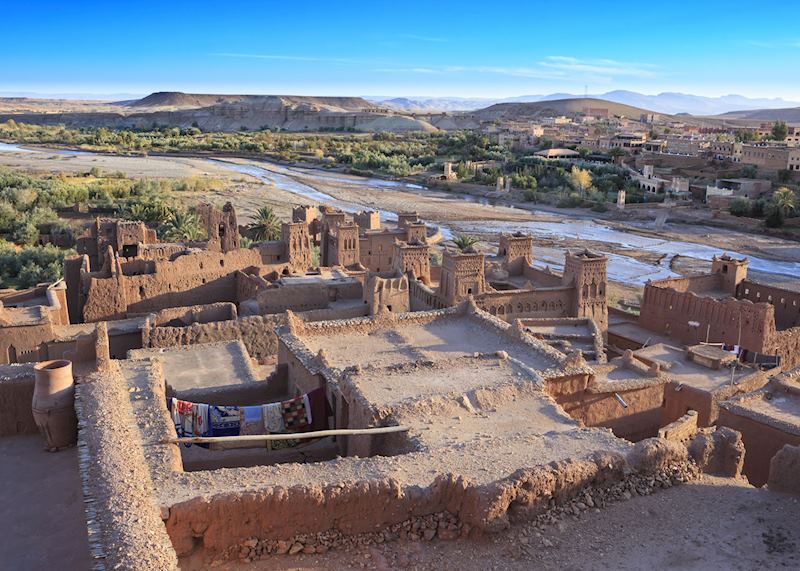

The ksar of Aït Benhaddou

A three-hour drive north of Zagora, Aït Benhaddou is the area’s best-preserved ksar (fortified towns that used to dot the ancient caravan routes). A handful of families still live here, maintaining the earthen buildings that date back at least to the 11th century.

On my last visit I was met by Omar, a young man in his early 20s who was sporting a wide-brimmed straw hat to keep off the sun. As a member of the one of the ksar’s resident families, he seemed to know everyone, and we often paused for him to introduce me to a cousin or friend as we wandered through the dusty streets.

The kasbahs (merchant homes) stand close together, their high mudbrick walls casting deep shade on the narrow street below. The buildings might be familiar to cinephiles — they’ve served as a setting for films since the 1960s, appearing in Sergio Leone’s Sodom and Gomorrah, The Last Temptation of Christ, Gladiator and The Mummy. Aït Benhaddou also stood in for Yunkai in Game of Thrones.

Read more about trips to Morocco

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Morocco