Small-sized engines running on slim tracks, India’s first mountain railway was playfully referred to as a ‘toy train’ by Darjeeling residents. The name stuck, and India’s network of narrow-gauge trains are all now affectionately known by the moniker. Traversing the foothills of the Himalaya and Tamil Nadu’s tea-covered valleys, these sturdy locomotives offer access to areas once reserved for determined pony carts and hikers.

Darjeeling Mountain Railway

By India specialist Graham

While pacing the platform waiting for the arrival of Darjeeling’s toy train, my guide recounted the inspired moment behind the railway’s design.

As the story goes, in the late 1800s a representative of the Eastern Bengal Railway, Franklin Prestage, was dancing with his wife at a society dinner. He’d been mulling over the engineering challenges of building the Darjeeling Railway when his wife reprimanded his dancing for stepping forwards instead of backwards. This gave him the inspiration he needed — instead of trying to design the trains to climb upwards, he would zig-zag them backwards up each gradient in a series of switchbacks and loops.

I’m not sure of the truth in the story, but the original 96 km (60 mile) route is an engineering masterpiece. Awarded the Engineering Heritage Award and UNESCO World Heritage Site status, as well as having its own dedicated society of railway enthusiasts, the Darjeeling Mountain Railway is arguably India’s best known, and most revered, toy train. Modern diesel locomotives now handle most of the schedule, but there are a couple of routes where you can still ride on a British-built steam train.

Riding Darjeeling’s toy train

The route originally ran from Siliguri Town — now replaced by the nearby New Jalpaiguri Station — right into Darjeeling. Landslides have since damaged parts of the track, making it impossible to ride the route in its entirety.

In my opinion, the best part of the route is still intact and runs like clockwork. A B-class steam locomotive departs from Darjeeling daily, journeying for forty minutes to Ghoom, India’s highest train station at 2,225.7 m (7,407 ft).

I arrived at Darjeeling Station to find the well-polished blue train waiting, its plume of smoke carried away on the wind. It sets off slowly and doesn’t quicken. Residents from homes and shops laid next to the tracks quickly cover washing and move crates of produce to let the train pass.

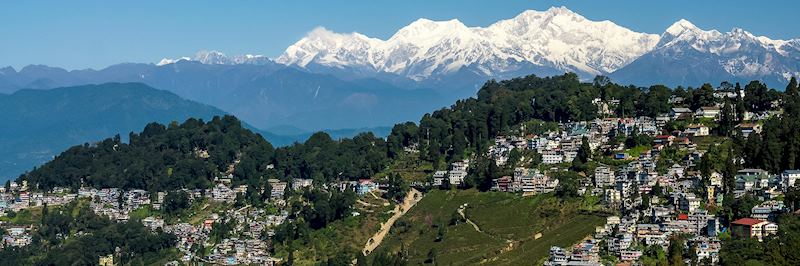

The train circles the Batasia Loop — an example of Prestage’s inspired engineering — before grinding to a halt. A small platform has been built here to let visitors disembark to take photographs of the train and its driver, who stands to attention alongside. On a clear day you can see the brightly painted roofs of Darjeeling spread out below and Kanchenjunga, the world’s third highest mountain, in the distance.

The train then continues on to Ghoom, where I suggest you disembark (you can ride the train back to Darjeeling if you wish). Ghoom has a small but vividly painted monastery that’s open to visitors containing a 4 m (15 ft) high Buddha. Depending on the monks’ schedule, you might catch their late-afternoon prayers. It’s then a two-hour drive back to Darjeeling.

There’s a scheduled daily steam train journey from Kurseong (about halfway along the route) to Darjeeling, but I’ve encountered enough cancellations and bad delays with this train to say it’s best avoided unless you have a very flexible agenda.

Getting to Darjeeling

Darjeeling lies in the northeast of India, sandwiched between Nepal and Bhutan, at the foot of the Himalaya. It’s best reached by a short domestic flight from Delhi or Calcutta to Bagdogra, the nearest airport. From Bagdogra, it’s a steep four-hour drive past tea plantations and hamlets to reach Darjeeling.

What to see in Darjeeling

Darjeeling may have been a British hill station, but its position between Bhutan and Nepal has stopped it becoming as anglicized as other colonial outposts. Buddhist monasteries lie alongside Anglican churches, and Tibetan handicraft stores trade next door to British bookshops. You can while away hours around the narrow streets and main square.

The Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, started by Tenzing Norgay, displays memorabilia and photographs from many epic expeditions. The nearby Himalayan Zoological Park is one of the only places where you stand a chance of seeing the indigenous red panda in India and has a well-reputed snow leopard breeding initiative.

The Kalka–Shimla Railway

By India specialist Sophie

Starting in Kalka, a transit city north of Delhi, the Kalka–Shimla railway winds for 96 km (60 miles) up the Himalayan hills. The route was completed in 1903, 22 years after the Darjeeling Mountain Railway, after engineers determinedly wound the track through 103 tunnels and over 864 bridges to its final destination: Shimla.

When the new line opened, the summer capital of British India boomed as it became possible for officials to take their families with them. Boarding schools, churches and performance halls were quickly built alongside a flourishing railway colony, home to the hundreds of workers it took — and still takes — to run the line.

Riding the Kalka–Shimla Toy Train

The route, with a few minor alterations, is still running in its entirety. A British fondness for paperwork and bureaucracy remains — systems haven’t changed in 100 years — resulting in remarkably punctual trains.

I followed in the footsteps of British civil servants seeking cooler climes, by starting my journey from Delhi. The Shatabdi Express leaves the city in the early morning, crossing the grassy plains of Haryana, until it reaches Kalka five hours later where you connect with the toy train.

The toy train’s steam engine has been retired, but the carefully painted diesel engine and red and cream carriages still carry an air of importance. It takes four hours to slowly climb 1,420 m (4,658 ft), stopping at a number of small stations along the way that mostly act as drive-through refreshment stops. I nipped off the train to grab a freshly cooked samosa and some chana dal (curried chickpeas), terrified the train would leave without me. It turns out the schedule leaves plenty of time to grab some refreshments. Barog Station, with the longest stop, is the best place to hop off.

The views, looking right down into the green valleys of the Himalaya, are interrupted regularly as the train dives into one of the many tunnels. The longest is 1 km (0.6 miles) long, and it takes a few minutes to re-emerge into daylight.

It’s worth getting your camera ready at Bridge No. 226, on the leg between Sonwara and Dharampur, as the train travels across a five-tier stone arched bridge.

The train usually arrives into Shimla in the late afternoon — I’ve occasionally caught the first signs of sunset from my carriage window.

What to see in Shimla

The city is built around a central square and many of Shimla’s streets are pedestrianized, making it easy to while away an afternoon wandering past the mock-Tudor bungalows and Scottish-influenced stone mansions.

Afternoon tea at Wildflower Hall, once home to the British military leader Lord Kitchener, is a luxurious affair. Sitting under beaded parasols on the hotel’s veranda, I was served dainty finger sandwiches, delicate cakes and a steaming pot of tea.

The Nilgiri Mountain Railway

By India specialist James

Like their counterparts in Delhi and Calcutta, Chennai’s British administration fled the sweltering heat every summer. Unfortunately for them, it was a long journey to cooler climes. Families would tackle the grueling journey 547 km (349 miles) west from India’s east coast up into the Nilgiri Hills to Ooty, the summer capital of the Chennai government.

Proposed in 1854 to make this journey more comfortable, the Nilgiri Mountain Railway was the first to begin operating — albeit only a small section of the route. The rocky terrain and thick forest caused a multitude of delays, preventing the line from being fully completed until 1908.

The line runs 46 km (28.5 miles) from Mettupalayam to Ooty, crossing 250 bridges en route. On the uphill climb, the locomotive is pulled up on a series of pinion wheels that bite into a notched track. Never reaching more than 45 km/h (27 mph), it boasts the steepest gradient of any railway in Asia.

Ooty sits in southern India at the point where the states of Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala converge. Much smaller than Shimla or Darjeeling, you’ll only need one night in Ooty before catching the train. I suggest incorporating Ooty and its railway into part of a longer itinerary, weaving through each region for a varied insight into south Indian culture.

Riding the Nilgiri Mountain Railway

I’ve always found that the timings of the downhill train, from Ooty to Mettupalayam, fit better into my travel plans than the reverse — the upward-bound train leaves very early in the morning. I left Udhagamandalam Station (Ooty is an abbreviation of the town’s official name, which only just fits on the sign) just after lunch, and arrived in Mettupalayam in the early afternoon.

The blue and cream carriages start the journey pulled by a diesel train, which meanders toward Coonoor, a station about halfway down the route. Sitting back into a thickly padded seat — I had secured a ticket for the first-class cabin — I watched thick forests of eucalyptus and tea plantations pass by. In Coonoor, the diesel engine is replaced by a steam locomotive, lovingly restored and maintained by a small team of enthusiasts who work at Coonoor Station. Just after we left Coonoor, the train stopped to pick up a gaggle of schoolchildren, dressed in uniforms that wouldn’t look out of place in a 1950s British boarding school.

The train then continues onward to Mettupalayam, entering a more subtropical climate of thick foliage and farmland. It passes a number of platforms, many not operational, stopping regularly to top up on water. The journey takes about four hours to arrive at Mettupalayam, a small transit town built to service the hill stations above.

There’s not much to see in Mettupalayam so I suggest driving onward to Coimbatore. From here you can further your railway experiences by catching the express train to Cochin. On the only railway line to pass through the Western Ghats, you’ll pass vivid green fields and rural villages before arriving into the palm-fringed rice paddies of Cochin.

How to get to Ooty

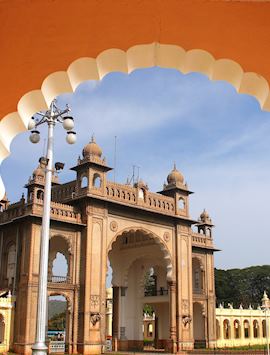

Bangalore has the closest international airport to Ooty, although it’s too far to drive in one day. The city of Mysore, three hours’ drive from Bangalore, is a convenient way to break up the journey. From here the powerful Wodeyar Rajas ruled for over 500 years, leaving a legacy of grand monuments and regal buildings. I recommend a few days here to walk up to the Nandi bull statue (the biggest bull statue in India) and take a boat ride through Ranganathittu Bird Sanctuary. Ooty is then a four-hour drive from Mysore.

Practicalities of riding on India’s mountain railways

- Due to their mountainous locations, the tracks are often affected by heavy snowstorms in the north or tropical downpours in the south. October through to April (avoiding the heavy snow in January and February) is a good time to travel to avoid these weather extremes.

- The mountainous regions of India can often be surprisingly cool compared with nearby lowlands. Pack warm clothing for the evening, when the temperature tends to drop.

Start planning your trip to India

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in India